All work and no play? The new ‘uni’ experience

Matthew Engel

Sep : 12 : 2017

Clark Kerr, president of the University of California in the years of campus turbulence in

the 1960s, famously defined the secret of running a successful university as providing

football for the alumni, parking for the academics and sex for the students.

His modern equivalents might say that nothing has changed, though for their British

counterparts, a different sort of football has a different role. University life has,

however, undergone astonishing changes since Kerr’s time. In Britain this has happened

largely by stealth. Universities were once essentially independent bodies funded by

government. Now that funding has largely dried up; they have to make a profit or risk death.

Privatisation of Britain’s utilities prompted intense controversy; privatisation of its

institutions devoted to study, knowledge, inquiry and debate has happened with barely a

peep. Fifty years ago a gilded generation of students spent their time protesting against

anything and everything, often for no obvious reason. Their grandchildren, facing an

infinitely tougher world, with everything to protest about (and in many cases blame their

forebears), instead take their medicine with infinite docility.

In his new book Speaking of Universities, the Cambridge don Stefan Collini says there is a

“hideously plausible” future in which “the dominant character of higher education

institutions across the world would be as businesses specialising in preparing people to

work in businesses”. It is a view shared by many hacked-off academics, their own

once-enviable lives made more insecure by sometimes contradictory pressures.

The students? They seem far too busy trying to get their degrees and a job to worry too much

about the future of their universities.

***

No one university can be described as typical, but the University of Leicester might stand

as a British representative: not quite old, not quite new; not world-famous but quietly

respected. It was founded in 1921, as a living memorial to the war dead, and was given full

degree-awarding status in 1957. It is proud of Sir Alec Jeffreys, who developed genetic

fingerprinting and DNA profiling here; proud of its involvement in the discovery of Richard

III in a city car park; proud of its space research — and proud too of its new business

school, which moves to a fancy new HQ next year.

Leicester has a pleasant campus, not far from the city centre, with most of the

accommodation a short bus or bike ride away in one of the nicest suburbs. Everyone is

friendly. But universities are no longer judged by vague perceptions, they are ranked. And

Leicester is not considered tip-top.

It is 25 years since John Major’s government, in a fit of egalitarianism, elevated all the

downbeat, mostly technically oriented, polytechnics to university status, and Britain’s 46

universities magically multiplied to 140. Not long before that, about 3 per cent of the

age-cohort went up to “varsity”; now about two-fifths go to “uni”.

But, far from creating equality, the expansion transformed what was once a vague pecking

order into a set of almost Hindu gradations marking the layers between the Brahmins and

untouchables. In the UK rankings Leicester finishes 25th, 26th, 33rd or 47th, depending on

which table you believe. In the world it is either 172nd, just behind Cologne and

Gothenburg, or 239th, just behind Tufts. There is even a sexual harassment league table,

though in that Leicester can proudly claim to be in the relegation zone, with no allegations

in the past five years.

However, it is not a member of the Russell Group, the self-selected group of what claim to

be Britain’s elite two dozen universities. This, explained Paul Boyle, Leicester’s

vice-chancellor, is simply because the occupant of his chair at the group’s inception in the

1990s was also chairing the umbrella body for all the universities: he felt he could not be

disloyal and join what might be seen as a cabal. That honourable decision now hurts like

hell. “My friends at home all look down on me because Leicester’s not Russell Group,” one

student told me.

Leicester did come top of one league table in 2016, and that matters, too. Its soccer team —

the city’s, not the university’s — famously and astonishingly, won the Premier League. And

this did coincide with a spike in applications. In particular, it seemed to help create

awareness in China. And China now really matters.

***

From the 1960s to the 1990s British university tuition was free, with a means-tested

maintenance grant on top. Except in Scotland, all that has been swept away. The state

subsidises science teaching, but little else. Undergraduates pay ?9,000 in fees; including

living costs as well, students expect to be more than ?40,000 in debt by graduation, before

even thinking about getting on to Britain’s mountain-high housing ladder.

These students are no longer a vague group of nuisances occasionally interrupting their

lecturers’ pet projects and port-drinking. They are the customers. In the admin building the

language of business suffuses everything: the leadership team has strategic conversations

with stakeholders about institutional transformation. The old titles persist, but

vice-chancellor, provost and registrar only lightly disguise the chief executive, his deputy

and the chief operations officer. “We have to be business-like,” insists the

vice-chancellor. “We have to think about the implications of what we do. But the mission of

the university is absolutely a scholarly and educational one.” On a turnover of almost

?300m, Leicester made a profit of ?1.5m in 2015-16; that, he says, will all be ploughed

back. He wants to keep the subject-range both broad and flexible.

But that profit is by no means secure. On one estimate only a quarter of Leicester’s income

comes from the state; more than half comes from tuition fees. Unlike a bank, the University

of Leicester is not too big to fail. And, in common with all its “provincial” counterparts,

it has been very slow building up a war chest from graduates who went on to get rich. In

contrast to American universities, sport was never for the alumni; it was recreation not

glory. Outside Oxbridge, British universities have never created a sense of institutional

loyalty and this is now proving a disastrous failing. “We’ve got 100 years of catching up to

do,” sighs Chris Shaw, who is in charge of Leicester’s newfound notion of alumni relations.

Paul Brook, an associate professor of sociology within the business school, is also the

Leicester co-secretary of the academics’ union, the UCU. And he is very worried about the

effects of the emphasis on money, especially on his members: “There’s an increasing sense

that we’re in football. Are you going to make the first team? Will you make a star striker?

Are we Premier League or Championship?”

Lecturers now face previously unknown pressures, on the one hand to produce significant —

and preferably lucrative — research but also to be great and indeed popular teachers, since

one of the most important tests is the National Student Survey. “Alec Jeffreys had a

beautiful obsession about fingerprinting DNA,” says Brook. “You’d just never be able to do

that now. That wonderful chaotic creative urge becomes managed away when you get measured

against performance indicators. Universities are supposed to be full of mavericks.”

An anonymous blogger in a samizdat newsletter, tellingly entitled Turbulent Times, specifically

blames the new business school: “It does produce knowledge to be sent out into the world, but

its knowledges are also increasingly being used to restructure the university itself. Indeed, it

might be said that the business school is the cuckoo in the nest, gradually reshaping what the

university is, redefining academic function and purposes?.?.?.?B-School knowledge provides a

template for how the university can become a global knowledge corporation like any other.”

An anonymous blogger in a samizdat newsletter, tellingly entitled Turbulent Times, specifically

blames the new business school: “It does produce knowledge to be sent out into the world, but

its knowledges are also increasingly being used to restructure the university itself. Indeed, it

might be said that the business school is the cuckoo in the nest, gradually reshaping what the

university is, redefining academic function and purposes?.?.?.?B-School knowledge provides a

template for how the university can become a global knowledge corporation like any other.”

This kind of criticism hurts Professor Zoe Radnor, the dean of the business school. And she cites her own academic background, in the study of service management: “helping public services become more efficient”.

“We are not training providers,” she insists. “We are educators. Our role is to allow

individuals to be reflective and critical. We are not afraid to ask questions other business

schools might be afraid to ask.”

Radnor accepts that the major importance of a business school is that it makes money, due to

its ability to bring in foreign (which, at least until Brexit means non-EU) students,

largely from China, who pay more. Seven per cent of Leicester’s students are Chinese; in

Radnor’s domain that rises to 15 per cent; and it is now establishing a campus in the

Chinese city of Dalian. “You need to understand which parts of an organisation are

moneymaking so you can run the rest of the organisation,” she says.

***

Turbulent Times is nothing to do with the students at Leicester. Indeed, the student union

seems as turbulent as the average cathedral. My own university memories are of a building

filled with contending causes and cigarette smoke, the walls filled with society

noticeboards, the floor full of screwed-up paper. Leicester no longer even has a main union

bar: it closed through lack of interest.

Much is made of peer pressure on students to play hard in the social media age. But in the

Leicester student union the atmosphere is calm, sanitised, earnest. The focal point is a

very pleasant food court, and the centrepiece of that is a Starbucks. In the late afternoon

a few students sat around, mostly staring at laptops or phones, fortified by coffee or

bottled water.

Most of the slogans, far from being revolutionary, are exhortations advertising the

orthodoxies of the era: “SOME PEOPLE ARE TRANS. GET OVER IT!” says a poster in one office.

The few leaflets lying around mostly advertise the availability of help: the Academic Advice

Centre, the Mental Health Drop-In Clinic; the Peer Mentoring Scheme. “Submitting mitigating

circumstances is straightforward,” says one notice. “And we can help.” The recognition that

student life can breed lonely despair was long overdue.

At lunchtime, incomers had to run a very polite gauntlet of a handful of students at three

trestle tables, two of them looking for sports club recruits; one selling spring rolls for

charity. There are still about 170 clubs and societies, none of them spectacularly original.

This is the age of political multi-polarity but the top choices for the politicised minority

are boring old Conservative and Labour. “I think the number one sport is quidditch,” sighed

one lecturer. “Tells you all you need to know, doesn’t it?”

Even one of the university’s most senior officials expressed concern about the students’

tendencies towards conformity and disengagement. “Students should, as part of their

experience, be engaged with the wider political issues,” says Dave Hall, the registrar.

“You’ve got an opportunity at university to explore ideas and be heard in a kind of

protected environment. And they’re not doing it very much.” There was an attempted sit-in,

apparently, but the room was already being occupied for a lecture, so the protesters just

drifted away.

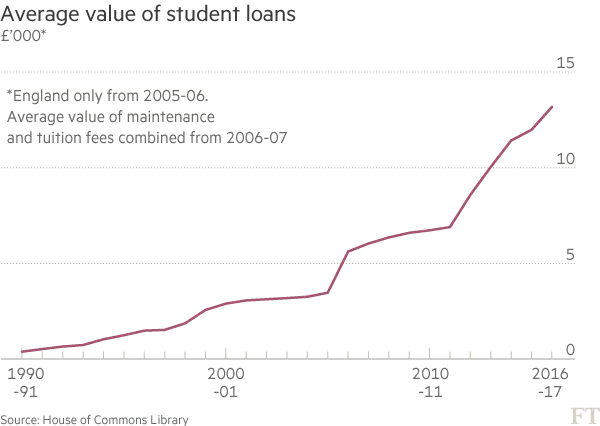

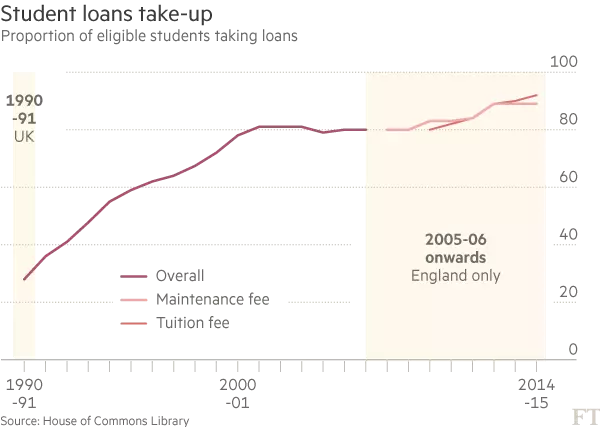

The explanation seems to be surprisingly simple. Tuition fees have ratcheted upwards from nil to ?1,000 to ?3,000 to ?9,000 over the past 20 years, a very deliberate redistribution of funds from students, who don’t have money yet, to older taxpayers who do. Most now have to take out loans to get through, before they even have to think of a mortgage.

Rachel Holland, now the president of the union, came up to Leicester herself the year before Nick Clegg infamously broke his promise to stop the most recent rise. She noticed a huge difference in attitude between the last ?3,000 cohort and subsequent intakes.

“I started hearing people say, ‘I paid ?120 for that lecture!’,” she recalled. “The attitude now is that the degree is more important than the university. That became seen as just a means to an end. I think people now come to university with a purpose, and they are so focused they don’t participate as much. Universities have become about getting a job at the end of it.”

This is backed up by Dr Rob Dover, now an associate professor in the politics department, who was among the last free intake at nearby Nottingham: “Thinking back on it now, there was an element of consumerism around those paying ?1,000. I remember a lecturer replying to one student that these fees were a bargain as they were far cheaper than private schools.”

In this new world the (very impressive) library has replaced the bar as the most significant point of the campus. There the caf? stays open to 10pm, rather than 6pm in the union. Indeed, near exam time it becomes a 24-hour building. Collaborative working is commonplace, and a group of second-year geology students were happy to break off and chat. But their aims were very clear. “A lot of the focus is on the work,” explained Hester Claridge from Cornwall. “I don’t want to go back to my parents and tell them I’ve got ?46,000 debt and no degree.” Yes, they all said, there was social life and fun — though for them it was mostly centred on the interest groups: music, rugby, maybe quidditch.

Go-getting vice-chancellors; disgruntled dons; conformist, consumerist, eager-beaver students. This is not the world of Clark Kerr. Or even of Porterhouse Blue or Lucky Jim. You might still find dons in sports jackets with patched elbows; the student uniform is still scruff and denim. But underneath the carefree ways have been swept away.

Perhaps the most publicised aspect of student discontent revolves round the stamping-out of heterodoxy: de-venerating the discredited dead or no-platforming the controversial living. My sense is the censoriousness represents a mere fragment of student opinion; most have more immediate concerns. But is it also absurd to wish that modern students had about them more heterodoxy of their own, more oomph, more sass, more rebellion, more individualism, more breadth, more sheer bloody unreason? Maybe Zoe Radnor’s business school can help teach such things.